Saving the orchids

Karin and Carlos check out an Earina mucronata at Ōtari-Wilton’s Bush. Photo: Kathy OmblerNationally significant research to save rare native orchids is being undertaken in a tiny science lab at Ōtari-Wilton’s Bush in Wellington.

Karin and Carlos check out an Earina mucronata at Ōtari-Wilton’s Bush. Photo: Kathy OmblerNationally significant research to save rare native orchids is being undertaken in a tiny science lab at Ōtari-Wilton’s Bush in Wellington.

Finding Ōtari conservation and science advisor Dr Karin van der Walt and research technician Jennifer Alderton-Moss is a bit of a mission. The pair work from a small cottage behind Ōtari’s plant nursery, hidden from visitors who wander the trails exploring New Zealand’s single largest collection of native plants.

Yet they are delighted to have this laboratory. Until recently they’d been squashed into a portacom. Community funding plus an Environment and Heritage Lotteries grant enabled them to move and equip what is now called the Lions Ōtari Plant Conservation Laboratory. They are now well set up to pursue their science conservation work, including ground-breaking orchid research.

The pair are working with Dr Carlos Lehnebach, Te Papa Botany Curator and native orchid guru.

As a student of botany, Chilean-born Lehnebach was so impressed when he saw a book on New Zealand orchids he came here to complete his Master of Science. Now he oversees studies and taxonomy of the massive orchid collection at Te Papa. For Lehnebach it’s an absolute treasure chest: thousands of orchids ranging from as-yet unnamed species to specimens collected by Solander and Banks in 1769. “These were on the Endeavour,” he says, eyes shining as he lifts them carefully from the vault.

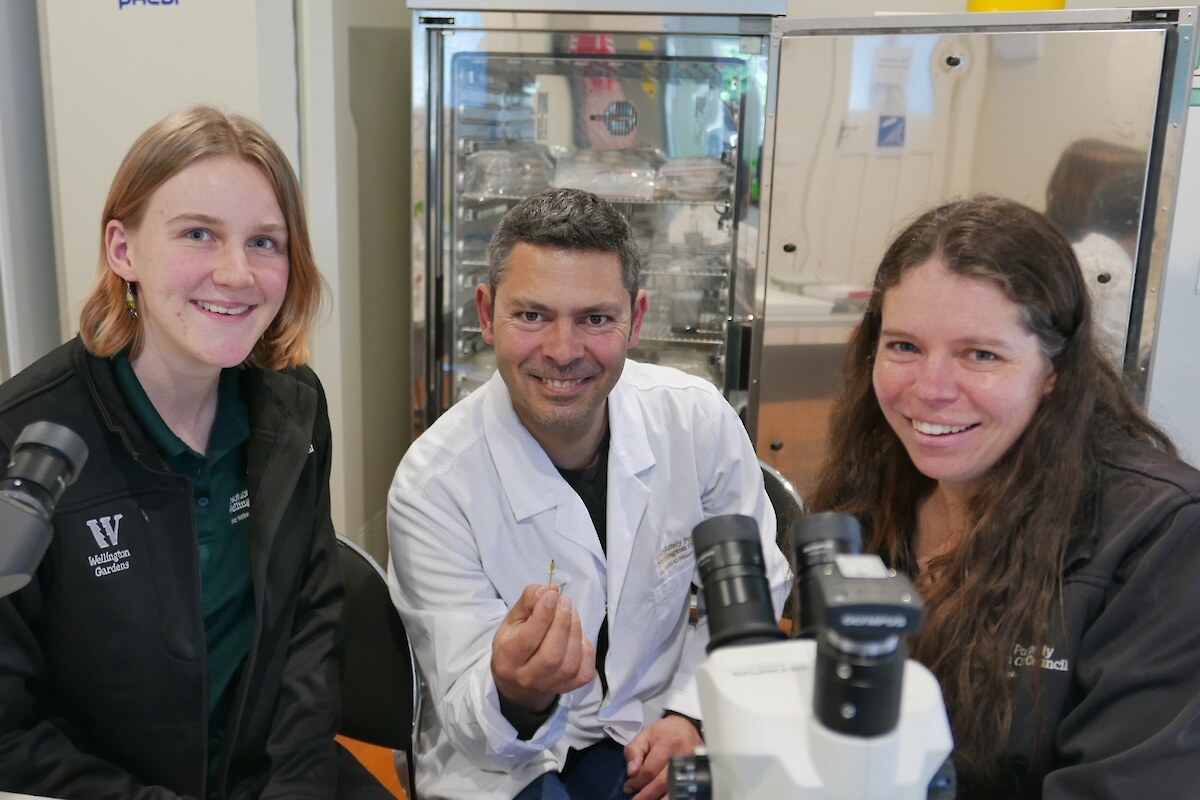

Orchid conservation scientists in the Ōtari lab, from left Jennifer Alderton-Moss, Dr Carlos Lehnebach, Dr Karin van der Walt. Photo: Kathy OmblerLehnebach says scant native orchid conservation work has been done in New Zealand, and a number of species are acutely threatened. “With this facility at Ōtari, Karin and Jennifer can now prioritise their research into these very rare orchids. Specifically, we are looking at how we can germinate and store their seed before they go extinct. So Ōtari now is leading the way in the conservation of orchids.”

Orchid conservation scientists in the Ōtari lab, from left Jennifer Alderton-Moss, Dr Carlos Lehnebach, Dr Karin van der Walt. Photo: Kathy OmblerLehnebach says scant native orchid conservation work has been done in New Zealand, and a number of species are acutely threatened. “With this facility at Ōtari, Karin and Jennifer can now prioritise their research into these very rare orchids. Specifically, we are looking at how we can germinate and store their seed before they go extinct. So Ōtari now is leading the way in the conservation of orchids.”

Native orchids are complex, says van der Walt. “They need a fungal partner to grow, and even if orchids grow surrounded by lots of fungi, only one can trigger seed germination. It is our job to find the right one.”

Despite the ‘needle in the haystack’ complexity, there have been successes. “We have germinated 16 seedlings of the rare swamp helmet orchid (Corybas carsei), which is found only in the Whangamarino Wetland, and six of the black potato orchid (Gastrodia cooperae), now known at only two sites in the wild. We have also been propagating other more widespread orchid species, which we are using as surrogates.”

This is ground-breaking progress, says Lehnebach. “Karin thinks outside the square, she has developed a method to germinate the seeds that has not been done before. It’s early days yet, however. Now she has these tiny seedlings, each two millimetres in length, the challenge will be to get them out of the Petri dishes and into the right type of soil.”

Alderton-Moss has been working with several orchid species, including the swamp helmet orchid, says Lehnebach. “By using DNA analyses, she’s been able to assess the entire fungal diversity in the orchid and the soil where it lives. She has also managed to isolate some pieces of fungi from the orchid to grow in the lab.

“Now we are looking to pinpoint which is the right fungus to trigger germination. This orchid was once widespread in the wild and is now only known in one place. That is why it is so important to propagate it, to establish a backup here at Ōtari and to grow new plants so we can place them in the habitats where they used to be.”

A tiny, five-month-old Corybas carsei seedling.Conservation science research in the Ōtari lab is not restricted to native orchids. Other projects have included a study of the nationally critical white-flowering Metrosideros bartlettii (Bartlett’s rātā or rātā moehau), pollen conservation protocols for the rare and parasitic flowering plant Dactylanthus taylorii (wood rose), and seed banking of Agathis australis (kauri), with Ōtari volunteers assisting with seed processing. Van der Walt is also working with Dr Debra Wotton on germination trials of the critically endangered Castle Hill Buttercup, and with college student Ryan Gordon on seed banking options for the critically endangered Lophomyrtus obcordata (rohutu).

A tiny, five-month-old Corybas carsei seedling.Conservation science research in the Ōtari lab is not restricted to native orchids. Other projects have included a study of the nationally critical white-flowering Metrosideros bartlettii (Bartlett’s rātā or rātā moehau), pollen conservation protocols for the rare and parasitic flowering plant Dactylanthus taylorii (wood rose), and seed banking of Agathis australis (kauri), with Ōtari volunteers assisting with seed processing. Van der Walt is also working with Dr Debra Wotton on germination trials of the critically endangered Castle Hill Buttercup, and with college student Ryan Gordon on seed banking options for the critically endangered Lophomyrtus obcordata (rohutu).

“While we base our work on science and research, I personally feel strongly that it has to be not just on the basis of academic research but also about conservation,” says van der Walt. “Ōtari is perfect for this; there is huge value in working here in this native botanic garden, so many of the species are already here and there is such a strong mandate for the conservation of native plants.”

The late Dr Leonard Cockayne would be chuffed to hear this. In the early 1900s, the eminent botanist was so distressed about the destruction of New Zealand’s native flora that he embarked on an ambitious project, gathering native plants from all around the country to protect them in one native botanic plant ‘museum’, at Ōtari. The result has been the conservation and cultivation of more than 1200 species, and today Ōtari-Wilton’s Bush, encompassing the native collections and 100ha of native forest, is recognised as an internationally significant native botanic garden.

Cockayne’s vision for Ōtari continues, not just in the native botanic garden but also in the science lab.

This story was originally published in Wilderness Magazine.

Posted: 15 December 2022